In the Siberian tundra, queer folks face conservative attitudes, constant harassment and violence. As a result, the region’s few LGBTQ+ activists struggle to meet their community’s needs.

A small show of support in Siberia. reassure. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

To this day, Yevgeniy Glebov doesn’t know how the two strangers found his address. Secure in his apartment, he heard a knock at the door. He opened it. They asked, “Aren’t you that gay activist?”

Yevgeniy needed to go to the hospital to recover from his injuries. After he reported the assault, the police closed the case without looking for a suspect. He expected little else from the authorities in Irkutsk Oblast, the Russian federal subject deep in Siberia where he lives and works. His NGO “Time to Act” provides legal, psychological and HIV prevention resources for the region’s LGBTQ+ community. However, this work also puts a target on his back. Advocating for gay rights is mostly a thankless job, demanding secrecy. For most LGBTQ+ Russians, it’s safer inside the closet than out.

Gay pride hasn’t yet reached the mainstream in Russia. Homophobia runs rampant in Russian society and riddles the country’s laws. Article 148 of the Russian criminal code gives prosecutors the license to claim any violation of religious practice as a crime, giving them a cudgel against gay rights groups. In 2013, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin signed into the law a ban on “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations” designed to prevent children from viewing or learning about anything homosexual. These laws reflect widespread disdain and discrimination against queer folks. The bill passed the State Duma with unanimous support.

Anti-homophobia demonstration in Russia. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Homophobia is less rampant in the cultural capitals of Moscow and St. Petersburg. There, gay clubs, beaches and bookstores thrive because of a highly concentAnti-homophobia demonstration in Russia. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.rated LGBTQ+ community. On the other hand, in Siberia, the presence of gay life diminishes as the threat of hate-fueled violence increases. Gay men have been lured to online dates in remote locations only to find a violent gang of homophobes when they arrive. Police have been known to abuse queer people as well. Yevgeniy once drove to nearby Angarsk after a supposedly gay boy had been brutalized by two strangers. When he arrived, the police had arrested the boy to accost him about his sexuality, letting the attackers go.

This environment demands a different approach to LGBTQ+ activism than in Russia’s European part. There, activists like Nikolay Alexeyev vociferously demand their rights. Alexeyev organized the first Moscow Pride parade in 2006, which then mayor of Moscow Yuri Luzhkov deemed “satanic.” The participants in the small parade faced arrests from the police and attacks from Neo-Nazis, but the subsequent, yearly demonstrations made Alexeyev the public face of the gay rights movement. He frequently brings his combative style to TV debate shows. On such a show, he grew so frustrated with a fancifully-hatted woman decrying “homosexual extremism” that he called her a “hag in a hat” and left.

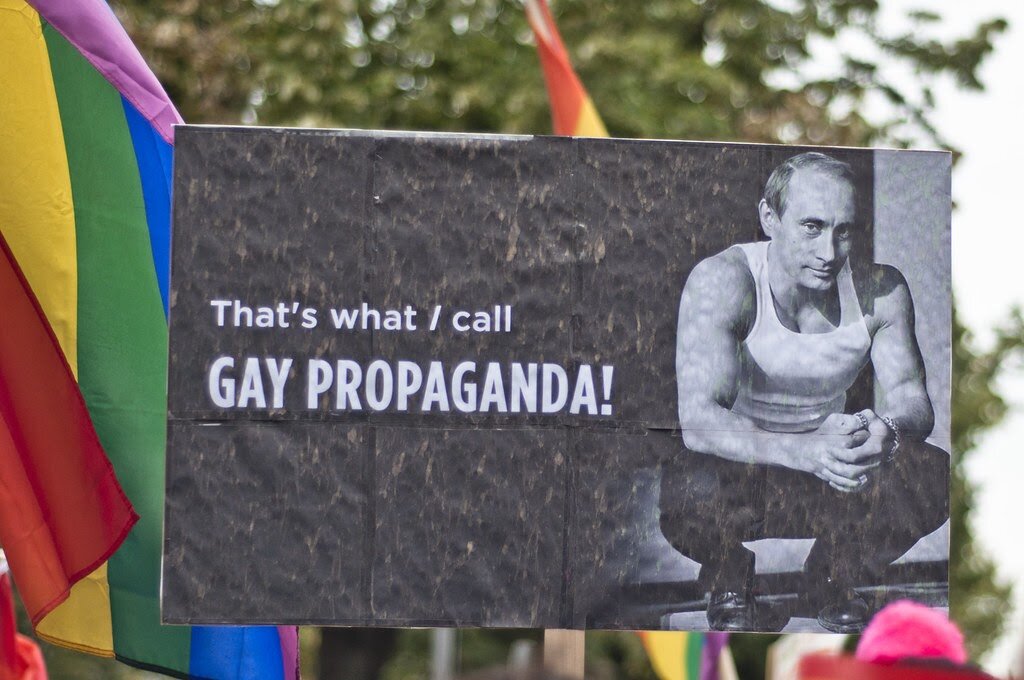

A protest placard mocking Putin. Marco Fieber. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Alexeyev often makes life difficult for gay activists in far-flung areas of Russia. Yevgeniy claims that the Russians he interacts with on a daily basis aren’t ready for Pride festivals, and that his pugnacity alienates those they need to win over. Irkutsk Oblast is home to 2.5 million people, but only forty LGBT activists, Yevgeniy estimates. His work with Time to Act doesn’t even pay. For money, he works at a local bakery.

A long road lies ahead for Yevgeniy and his fellow activists. LGBTQ+ folks remain political untouchables across the Russian political spectrum. Even Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most powerful foe, does not touch the issue of gay rights. Amnesty International revoked his status as prisoner of conscience mainly because of his unapologetic xenophobia, but also because of his comments about the LGBTQ+ community. In a recent interview, Navalny repeatedly used a Russian slur to describe gay people.

In the Soviet era, gay folks, if discovered, were sent to gulags—brutal work camps that relied on the frigid tundra to stop prisoners from escaping. Queer artistic luminaries such as filmmaker Sergey Paradjanov and poet Anna Barkova were enslaved there, leaving a legacy of queer survival. Their spirit invigorates LGBTQ+ activism in Russia; it is sorely needed. Although gulags now sit empty, queer Russians too often find their only safe haven in the closet.

Michael McCarthy

Michael is an undergraduate student at Haverford College, dodging the pandemic by taking a gap year. He writes in a variety of genres, and his time in high school debate renders political writing an inevitable fascination. Writing at Catalyst and the Bi-Co News, a student-run newspaper, provides an outlet for this passion. In the future, he intends to keep writing in mediums both informative and creative.